Linda Kuhn

1/6

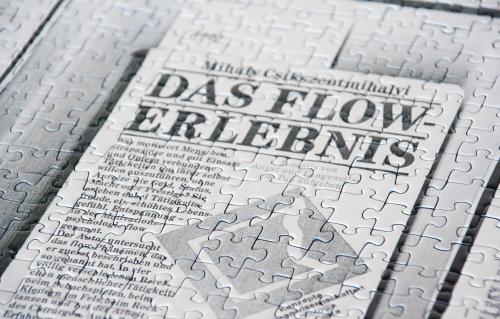

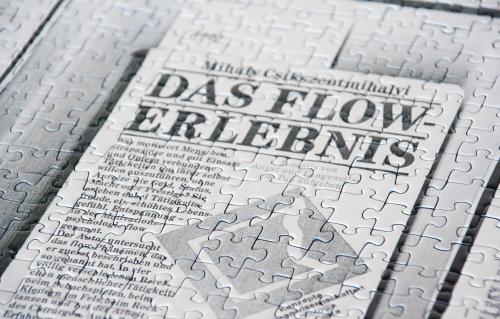

Linda Kuhn FLOW, 2015 Installation, 3 pieces, each with a jigsaw puzzle with 1000 pieces, wood, each between 70 to 90 x 86 x 66 cm. Photo by Cosimo Filippini

2/6

Linda Kuhn FLOW, 2015 Installation, 3 pieces, each with a jigsaw puzzle with 1000 pieces, wood, each between 70 to 90 x 86 x 66 cm. Photo by Cosimo Filippini

3/6

Linda Kuhn We dare to say many things at once 2015 installation, 6 watercolours in wood frames each watercolour 62,5 x 88 cm, Photo by Cosimo Filippini

4/6

Linda Kuhn We dare to say many things at once 2015 installation, 6 watercolours in wood frames each watercolour 62,5 x 88 cm, Photo by Cosimo Filippini

The Art of Being Lost in the Work of Linda Kuhn

In Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost – a beautifully written meditation on the relationship of getting lost and the art of living with uncertainty and mystery – the author quotes Thoreau: ‘Not till we are completely lost, or turned around, –for a man needs only to be turned round once with his eyes shut in this world to be lost, – do we appreciate the vastness and strangeness of nature. Not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.’ Getting lost, Solnit writes a little further on, is not about losing what is familiar, but rather, about the unfamiliar appearing. In other words, an experience of being lost, of losing our way; what we might call, in slightly different terms, a withdrawal from reality into a psychic state of ambiguity and non-purposeful activity, is essential to the discovery of self and empathetic receptivity to others.

From this perspective, subjected to what the ethical philosopher Emmanuel Levinas has called ‘the audacious dreams of a restless and enterprising capitalism’, the following question begs to be asked: At this very moment in time, do we have permission to engage in activities without immediate purpose or profit; that is, to be in the world otherwise and aimlessly? Perhaps we can extend this question even further: Is there room to get lost in the landscapes of our social and psychic worlds, mapped and adapted, as it were, by the array of sat navs, GPS, self-trackers, digital platforms and live status updates? Virtual voices of action haunt us from within, imploring us to ‘keep busy and carry on’. Like a motivational refrain they emanate from the internalized echo chambers of influencers, bloggers, vloggers and other manuals for improvement in all aspects of life.

Linda Kuhn’s diverse artistic work plunges us straight into the heart of some of these questions and beyond. Her subtle interventions and carefully constructed installations arguably put us in touch with a different experience of social time: time without explicit content and reason. Both Flow (2015) and Dimmer Party (2017) invoke atmospheres of play, alluding to the experience of getting lost in a time-space marked by ambivalence and impermanence. Flow presents a set of jigsaw puzzles which feature the texts written by Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who coined the concept of ‘flow’ in the 1970s to designate a feeling of complete absorption or concentration with a particular activity or situation. In Dimmer Party, the dimmable lamps, accessories, champagne glasses and background music emulate the languid mood of leisure and amusement. But a complexity lies beneath these deceptively playful surfaces – what might, at first glance, seem like a simple rendition of the conditions of entertainment – Kuhn’s artworks, it seems to me, go further by bringing into experiential relief the complex double nature of being lost. The immersive experience of the jigsaw puzzle or party, of which we are reminded at first, appears to be at variance with the felt uncertainty of our actual encounter with the work of art in the ‘here and now’ of the exhibition. Let me try and elucidate more clearly what I mean by this.

On the one hand, on the level of con- tent, Kuhn’s installations represent two kinds of doing where time recedes into the background: time is taken up, as it were, by the activity at hand (at the party, we get lost in the music, the softly dimmed light, the enjoyment of socializing, drinking, escaping into a world of satisfaction; similarly, while engaged in the jigsaw puzzle our attention is dominated by the occupation, consumed by the search for the missing puzzle piece); and yet, on the other hand, by placing a particular demand on our bodily and mental response to the environment as viewers, the works in themselves invite us into a very different relation to time and space, one which seemingly makes us feel out of sync with the represented experience. Standing within the installation, contra the actual activity, we are struck by the uncanny presence of time. The felt slowness of looking at the work of art – wondering what it means and where it is taking us – forces itself upon us, causing us to lose our way. Kuhn plays with our sense of time and space and in so doing brings the viewer into interaction with a plurality of temporalities, and greater awareness of the ways in which we structure our engagement with self and others relative to our experience of time and space.

Our daily lives and relations in the modern West are organized, indeed colonized, by the pressures of clock time. As writer and psychoanalyst Josh Cohen astutely points out, today the anxious demands for perpetual activity, be it work or leisure, are woven into the guilt-ridden fabric of existence. ‘Nothing is ever fundamentally “off” and there is never an actual state of rest’. For those of us living under the sway of this so-called ‘tyranny of doing’, the fantasy of total control looms large. Yet the promise of peace seems to hinge on a paradox: work frantically in order to get a break only so that you can remain active: to follow, like, upload, improve and adjust; to keep up to date with personal projects, exer- cise routines, diet regimes, latest Netflix series, political debates, the list goes on. In our modern consumer culture, as Cohen proposes, individuals operate an endless to do list in a constant fast forward mode. But what if we were to stop doing – controlling – and start being?

Kuhn’s idiosyncratic approach echoes this prevailing dilemma and challenges the privileged place afforded to the overactive and task-oriented life in our culture. Her creative practice furnishes us with valuable ways of thinking about the ways in which our social and psychic experiences are organized vis-à-vis technology, and what might go missing in our subjective experience of self and others as a result of this relentless distraction and choice. In the encounter with Kuhn’s works of art, time and pur- pose become suspended, as if to provide an intermediate region of being which sits boldly between states and within indeterminacy, resisting the violence of binary logic (off/on, right/left, male/fe- male, active/passive). This leitmotif also animates Kuhn’s piece We Dare to Say Many Things at Once from 2015, com- prising a series of delicate watercolors in which two different words with similar pronunciations are faintly embossed. Thrust into ambivalence when reading ‘No’ and ‘Know’, ‘Bye’ and ‘Buy’, for example, the viewer hovers on the edge of one meaning or another, and is never able to settle into the security of either. A neutral space opens up, liberated from the value-laden categories and presuppositions of meaning and purpose.

This gesture has political and psychological implications. It brings into focus what happens when we allow ourselves to stay with an experience and do not evade it by organizing it into the cognizable. Then, and only then, might something quite unexpected and novel about ourselves and the world of others slowly emerge inside us. Being lost, as Kuhn’s artistic works beautifully stage, to recall the words of Solnit, is to welcome what is unfamiliar within the familiar with empathy and thus be able to inhabit this space of uncertainty peacefully.

linda-kuhn.de

1/6

Linda Kuhn FLOW, 2015 Installation, 3 pieces, each with a jigsaw puzzle with 1000 pieces, wood, each between 70 to 90 x 86 x 66 cm. Photo by Cosimo Filippini

2/6

Linda Kuhn FLOW, 2015 Installation, 3 pieces, each with a jigsaw puzzle with 1000 pieces, wood, each between 70 to 90 x 86 x 66 cm. Photo by Cosimo Filippini

3/6

Linda Kuhn We dare to say many things at once 2015 installation, 6 watercolours in wood frames each watercolour 62,5 x 88 cm, Photo by Cosimo Filippini

4/6

Linda Kuhn We dare to say many things at once 2015 installation, 6 watercolours in wood frames each watercolour 62,5 x 88 cm, Photo by Cosimo Filippini